Migrant Literature

Sumaya Abdel Qader “Quello che abbiamo in testa”

(Mondadori, 2019)

Horra, an Italian woman barely under forty, the daughter of Jordanian Muslim parents, lives in Milan with her adoring husband and their two very different teenage daughters. Her life certainly can’t be called boring; on the contrary. As a perfect equilibrist, she juggles her days between family, work as a secretary in a law firm, university just steps away from completion, volunteering, prayers, and discussions at the mosque, and her colorful and diverse group of friends. Yet, despite the fatigue and daily challenges, despite the longing for the family far away, Horra can’t help but feel serene, even happy.

Ubax Cristina Ali Farah “Il comandante del fiume”

(66th and 2nd, 2014)

There is a legend in Somalia passed down through generations. Since their land was devoid of rivers and drinking water, the people entrusted two wise men with the task of creating a river. The wise men fulfilled the request, but the river also teemed with crocodiles—cruel creatures. Someone had to govern them to allow access to water, and the people chose a commander who had the power to annihilate the beasts if they didn’t obey his orders. Since he was young, Yabar has heard his aunt Rosa tell this story and learned that to understand good, one must coexist with the necessary evil. Eighteen years old, disinterested in studying but eager to provoke, Yabar lives in Rome with his mother, Zahra. His father abandoned them many years ago, and he keeps a photo of him made from clippings, where the man’s contours are indistinct and monstrous. The pain of abandonment doesn’t stifle Yabar’s curiosity about his father’s whereabouts, and his mother’s reticence hurts him. Sent in punishment to his aunt’s house in London, Yabar finds himself immersed in a unique Somali microcosm and discovers a terrible family secret, perhaps one he had wished to forget.

Ubax Cristina Ali Farah “Le stazioni della luna”

(66th and 2nd, 2021)

Orphaned by her mother, Ebla grows up in the Somali hinterland. Her elderly father, an astronomer and traditional diviner, teaches her the forbidden art of reading the stars, planets, and signs of the sky. To escape an arranged marriage, she finds herself in 1930s Mogadishu, aided by the poet and truck driver Gacaliye. Together, they set up a small but successful business and have two children, Kaahiye and Sagal. Ebla’s story intertwines with that of Clara, her wet nurse’s daughter, born to Italian parents living in Mogadishu. Forced to leave the country as a teenager with her mother and brother Enrico aboard one of the famous “white ships,” Clara will return to her hometown only in the early 1950s as a young teacher, at the dawn of the Italian Trusteeship Administration. Through her close relationship with Ebla, her children Kaahiye and Sagal, and her friend Mirella, Clara becomes personally involved in the struggles for the country’s independence during a turbulent historical period when Italy returns to Somalia with the task of guiding it through the path to independence.

Antonio Dikele Distefano “Chi sta male lo dice”

(Mondadori, 2017)

This is the story of Yannick and Ifem, the story of two young people—of loss, absence, abandonment, and how hard it is to believe in life when it takes more than it gives. A story that began in a neighborhood where it’s not just buildings falling apart, but also people without scaffolding, enslaved by economic hardship to the point of clinging to work and giving up on life. Where those who can’t cope drink themselves into oblivion and take it out on their children and wives behind closed shutters. Where everyone knows but does nothing, because they all carry the scent of poverty and the worn-out shoes of those who brake their bikes with their heels. A story of broken dreams passed down from parents to children—parents who left Africa for “na Poto”, Europe, without realizing this country is neither ready for their features nor willing to support their ambitions. Here, just having slightly darker skin makes you a target, different-shaped eyes make you an intruder, and a surname with too many consonants draws stares. In this desolation, Ifem tries to fill the emptiness consuming her with love—for Yannick. A boy who seems unstoppable. “Ifem, we won’t stop until they understand we’re not Black people who feel Italian, but Black Italians,” he repeats constantly. But gradually, that love, like everything around her, fades. What’s left is just a faint shadow in the imaginary lines she traces on his lips as he sleeps—one of the rare moments Yannick looks peaceful. Because his relentless drive is stopped by cocaine. It started out of boredom, almost by chance, in a working-class neighborhood where everyone tries it at least once—even priests. For a moment, the white powder fills every void—makes you feel like you’ve got all the steel of the Eiffel Tower inside—but then it takes everything away. “People who suffer don’t say it” isn’t just a punch to the gut; it’s above all a story of how flowers can grow even through concrete. Of how there’s always a way to save yourself—as long as you don’t give up, as long as you never stop loving life.

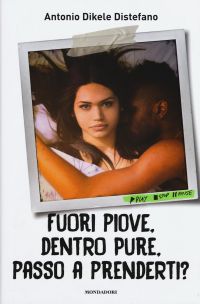

Antonio Dikele Distefano “Fuori piove, dentro pure, passo a prenderti?”

(Mondadori, 2015)

There is an important love story, one that lasted a year and was opposed by everyone—the first great love and its end. Because Antonio is Black, and to her parents, he’s the wrong guy. Then there’s Antonio’s family, his friends, school, and other matters of the heart. There are encounters, loves, moments that make you grow, and unforgettable instants. “It’s raining outside, inside too, should I pick you up?” is the life of a boy told in a rush, chasing emotions, moving from one image to another. Pages filled with feelings, phrases that strike the heart and beg to be written and rewritten. A story composed of singular moments, like individual songs, that together form the playlist of a life.

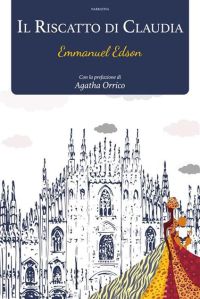

Emmanuel Edson “Il riscatto di Claudia”

(Indipendente, 2021)

Claudia is an orphan raised in the city of Milan, passing from one foster home to another until she is placed with an elderly widow without children. The constant relocations have not provided stability for the young woman, robbing her of the opportunity to receive an education. Yet she possesses a unique gift: her beauty. The only tool she has to escape her own misery. Her hope is to marry a wealthy man, but she soon realizes that what attracts men is only her body. After yet another disappointment, she decides to take matters into her own hands, using men in turn with the aim of becoming the most important person in the city.

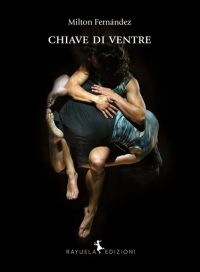

Milton Fernández “Chiave di ventre”

(Rayuela, 2017)

A young girl finds herself, without even being warned, standing before the examining board of a prestigious Classical Dance Academy. She is accepted and soon discovers she is destined to become a star—the realization of her mother’s dream (a dream her mother has imposed on her). A dream she is forced to fully immerse herself in, both body and soul. She must confront strict rules, an extreme and uncompromising discipline, the denial of pain and her own needs, and the submission of her body, shaped day after day in pursuit of the mirage of perfection.

Rania Ibrahim “Islam in Love”

(Jouvence, 2017)

The story of a forbidden love and passion between Laila, a veiled anglo-Arab Muslim, and Mark, a non-Muslim, the son of an extreme right-wing party leader in the city of Dover. Laila tells her story with all her contradictions and insecurities, caught between two distant cultures. Sex, though forbidden, becomes the territory that the two protagonists naturally cross with the boldness of their eighteen years. They explore the submerged worlds they hold in their hearts, ready to face an intimate clash of civilizations. Laila and Mark strip away completely their symbols, unquestionable dogmas for our society, loving each other beyond these.

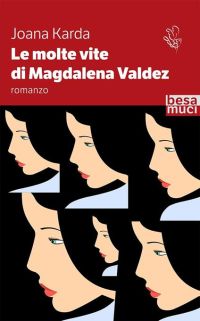

Joana Karda “Le molte vite di Magdalena Valdez”

(Besa Editrice, 2019)

Magdalena Valdez’s long journey begins in Carmona, India, at the end of the 1980s. Following an event that will shape her life, the young Maggie embarks on a journey that first takes her to the Soviet Union, then to the Rome of the Second Republic, and finally to post-Basaglian Trieste. In each place, the protagonist assumes a new identity: in Russia she becomes Lena, learning to manage her independence; in Rome, she is Maddalè, experiencing both the joy and frustration of stability; in Trieste, she becomes Mad, discovering her true self. A woman who changes and evolves at every step, nearly losing herself, only to find herself again once she confronts her past.

Gabriella Kuruvilla “Maneggiare con cura”

(Morellini Editore, 2020)

Diana, Pietro, Manuel, and Carla are the four protagonists of a polyphonic novel set during a Milanese August. They are in their thirties and forties and experience precariousness, particularly in their emotional lives. A decade ago, they all attended a funeral without knowing each other. Each of them has a different connection to the deceased, Ashima: Diana is her daughter, Pietro is her former student, Manuel is her former lover, and Carla was there simply to sketch the details of the attendees in a notebook. A decade later, their lives intersect and intertwine, depicting a present filled with uncertainties but also choices, constantly referring to the past. The book, narrating their stories in the first person with a fast-paced rhythm that alternates between dramatic and sharp irony, paints a portrait of the contemporary world while also shaping Ashima’s character: a figure that challenges many stereotypes surrounding the “typical” Indian woman.

Elvira Mujcic “Consigli per essere un bravo immigrato”

(Elliot, 2019)

You have escaped war, hunger, and the dangers of clandestine journeys. Now that you are finally in a place where you might have a chance to rebuild your life, you must convince a panel of strangers that you had valid reasons to endure all of it. Ismail, a young Gambian man, was not believed, and now he carries a piece of paper in his pocket stating that his story is not plausible. But why, Ismail wonders? What makes a life story convincing? Elvira, an Italian-Bosnian writer who arrived in Italy twenty years before him, asks herself the same question. From the intertwining of their lives emerges a narrative—on the edge of absurdity—about the unpredictable violence of bureaucracy. Moving through disappearances, nostalgia, and anger, with a stubborn desire to preserve their dignity and escape the immigrant stereotype, the two protagonists reflect, not without irony, on the power that draws the line between unbelievable truths and acceptable fictions, disregarding the fact that life often far surpasses imagination.

Masal Pas Bagdadi “Ho fatto un sogno”

(Bompiani, 2015)

Masal Pas Bagdad returns with stories of love and search, weaving between reality and dream, memory and recollection, tied to her family and her people. The old grandfather appears to the protagonist in the night, and his few words prompt her to reflect on her life and her children. In this extraordinary journey beyond time, Masal visits the Tel Aviv cemetery and brings its inhabitants to life as if by magic, walks through the alleys of the market where names and languages blend among refugees who escaped the Shoah and persecution. With nostalgia, she recalls the Damascus ghetto, filled with scents and stories of another era, where Tune, the child she once was, absorbs everything around her, unknowingly preparing to face the tragic events of her life. “I Had a Dream” is a journey through past and present, toward a future filled with love for life.

Masal Pas Bagdadi “Il tempo della solitudine”

(Bompiani, 2017)

The memory of affection, the longing for a kind word, the embrace of a loved one: these are the things that sustain the residents of the retirement home. More generally, they provide the strength needed to move forward in moments of fragility, allowing individuals to break free from loneliness. Masal Pas Bagdadi, with the sensitivity and delicacy that define her, tells the stories of the residents of a special retirement home that is at the same time very similar to others: a “five-star hotel” where guests live suspended in a timeless state, filled with memories of the past but also expectations for the Shabbat ritual and visits from close family members. With love and without dramatization, the author allows us to experience through the stories of this world (often kept at a distance and forgotten) the hidden richness of these characters, their warmth, and their need to communicate and be heard with care.

Lotar Sanchez Arcos “Il delitto delle cascine”

(Porto Seguro Editore, 2020)

Lamin is a young Gambian living in a reception center in Florence. The transition to adulthood, in a country far from his homeland, brings out a series of insecurities that he has never faced before. In this delicate phase, he finds himself needing to gather evidence to clear his friend Aboubacar, who mysteriously disappears after a body is discovered in the park of Cascine. Each step of this adventure awakens in Lamin many terrifying memories of his journey to reach Europe across the desert and the Mediterranean; even the educators at the reception center, who are trying to help the boy, find themselves confronting some ghosts from their own lives. “The Crime of Cascine” is both a mystery and an analysis of a controversial social phenomenon.

Igiaba Scego “Adua”

(Giunti, 2015)

Adua was born in Somalia, but at seventeen she fled, leaving behind a dictatorial regime and a strict father. She found refuge in Italy, in Rome, where she once again faced the challenges of pursuing her life goals and witnessed many others arriving in search of hope, like the young man who landed in Lampedusa and with whom she fell in love. Now, the civil war that devastated her homeland seems to have ended, her best friend Lul has returned to Mogadishu, and she feels torn between the call of her roots and the responsibilities of life in Italy. However, after her father’s death, Adua inherits the family home: perhaps it is truly time to return to Somalia, and maybe only by confronting the past can she open the door to building her future. The voices of a daughter and a father intertwine in these pages to tell a story that moves between Italy and Africa, between memory and dreams, delving into the many unresolved conflicts that shape our world and personal relationships. Igiaba Scego crafts one of the most captivating pieces of her exploration of colonial history: Adua is at once the story of a courageous woman, a grand family portrait, and a 20th-century saga of wars, migrations, and hopes.

Igiaba Scego “La linea del colore”

(Bompiani, 2020)

How many of us, stepping off a train today at Roma Termini, remember the Five Hundred to whom the square in front of the station is dedicated? It’s February 1887 when the news reaches Italy: in Dogali, Eritrea, five hundred Italian soldiers are killed by Ethiopian troops seeking to thwart their colonial ambitions. A wave of indignation sweeps through the city. At that moment, Lafanu Brown is returning from her walk: an American painter who has been a Roman citizen for years with dark skin. She is met with the crowd’s anger until a man rescues her. It is to him that Lafanu decides to tell her story: her birth in a Chippewa Indian tribe, the dark-skinned stranger who loved her mother and disappeared, the woman who allowed her to study but considered her ungrateful, abolitionism and violence, the meeting with her mentor Lizzie Manson, and the bold decision to board a steamship headed for Europe on a Grand Tour in search of beauty and independence.

Abdelmalek Smari “La trottola”

(Selecta Editrice, 2019)

The story follows a young Algerian, from a small town in the highlands, intertwined with the quirky yet very real tales of other men. His name is Nabil, and he is one of many young people with education but without jobs in today’s Algeria. Smari presents an unusual and thought-provoking Algeria: bricklayers dealing with the construction of a “dala”, a contested imam, street toughs, a veteran of the resistance, the black market for currency exchange, an outspoken gay activist. All are constantly engaged, along with daily challenges, in perpetual debates amongst themselves about everything and everyone. It’s a world away from the clichés we are accustomed to when thinking about a region of the world we know as strictly Arab. The story unfolds from beginning to end, following the trajectory of a spinning top, which also appears in the final scene in the hands of a young girl, woven with emails between the protagonist and his ambiguous, distant love.

Widad Tamimi “Il caffé delle donne”

(Mondadori, 2014)

Coffee is a constant in Qamar’s life: strong and bold as her mother drinks it, softened with a splash of milk as her partner prefers, or boiled three times, bitter and infused with cardamom, as she learned to drink it in Jordan. Qamar has always balanced between two worlds, though she only realized it on her fourteenth birthday. Until then, she had happily spent winters in Italy and summers in Jordan, staying with her father’s Muslim family. In the Great House on the hill, she listened to her grandmother’s tales of “One Thousand and One Nights”, savoring the spicy flavors of Middle Eastern cuisine alongside her father’s language; on the sunlit terrace, she experienced her first love. But on her fourteenth birthday, she officially became a woman. Separated abruptly from her friends and forbidden from mixed company, Qamar is forced to confront the profound differences between the two cultures she belongs to. Yet, during the long days spent with the women of her family, she learns to care for her body as every bride must, to cook, to be seductive yet modest. It is during these moments of shared femininity that she is introduced to the ancient, fascinating ritual of coffee. Grandmother, aunts, and sisters gather in the parlor to share confidences, sip the aromatic beverage, and glimpse their destinies. Each day, only one is chosen to have her grounds interpreted by Khalto Sherin, who reads in the sediment the secrets of the heart and the future. Years later, faced with the sorrow of unfulfilled motherhood, Qamar feels the need to reconnect with her roots and reflect on the words she once heard on the distant day she read her life in the grounds. Choosing the ingredients for her coffee, deciding its aroma and strength, becomes a metaphor for understanding the flavor she wants to give her days. The protagonist of this novel is a woman like all of us, searching for her identity and the essence that makes every life unique.

Widad Tamimi “Le rose del vento”

(Mondadori, 2016)

It is often said that the best place to begin a story is at the beginning. This is precisely what the author of this novel does: probing into the stories of her ancestors, tracing the branches of the family tree down to its roots. An unstoppable, vital impulse: “I feel indecipherable to myself. I lack the key. I retrace history backwards, searching for a home that feels like mine.” Weaving the fabric of her origins, Widad Tamimi takes us to the turbulent heart of the past century. She tells of a father, Khader, born in Palestine, in Hebron, in 1948, the same year that Israel was founded. The family had moved to Jerusalem in search of prosperity, but the war forced them to flee back to their hometown. They are poor, work the land, live in a room made of bricks and tin. Khader dreams of becoming a pediatrician to help the children of his land. In 1967, another war makes them refugees once again. They flee to Amman, Jordan. Further back in time, Carlo Weiss, the maternal grandfather, is born in Trieste in 1924. He is Jewish and proud to be Italian; the family villa is frequented by writers, musicians, and psychiatrists. Until 1938, when the situation for Jews becomes unbearable, Carlo and his family flee, first to Lausanne, then to London, and finally to the United States. Carlo returns to Italy in 1947, just months before Khader’s family is forced to flee from Jerusalem. He meets a woman, falls in love, and they have two daughters. Khader also arrives in Italy to study Medicine. He meets Carlo’s older daughter, beautiful and rebellious, and a powerful love blossoms between them. The first of their daughters inherits the complex legacy of displaced men and women, torn from their land, swept away by the relentless wind of History. With courage, determination, and an unceasing desire to repair the past in order to build the future, she follows the intertwined paths of two exiles, two destinies that tell us where we come from and ask us where we want to go.

Marilena Umuhoza Delli “Negretta. Baci razzisti”

(RedStarPress, 2020)

If your mother works, she must inevitably clean stairs. Or be a prostitute. If you walk alone on the street, you’ll be treated like one too. This happens if you’re a woman. Black. In Italy. Today. And it doesn’t matter if you were born in this country, because there will always be someone, upon hearing you speak, who can’t help but be surprised by your fluency in Italian… This occurs because the language of discrimination knows no subtlety. It adds to blatant racism a thousand opportunities for subtle disdain and concealed ignorance. This is the story of a girl who grew up being called “Negretta” and each day found the strength to face the wounds inflicted on her soul by sexism, contempt for the poor, and xenophobia. A struggle for the affirmation of an Afro-Italian identity that refuses to relinquish the weapon of irony, building a maze of unpredictable endings, essential passions, and awareness torn from the scorn of those who, page by page, from their machismo and more or less overt racism, will be forced to discover they’ve already been defeated by history.

Yousef Wakkas “Opera 99. L’autobus dei sogni”

(Indipendente, 2016)

Antonio Madera, a construction worker and a criminal on semi-liberty, almost without putting up any resistance, lets himself drift, accepting to take up once again the role of the subjugated in exchange for a survival and a whirlwind love that will gradually drag him towards failures from which he will no longer be able to escape. Only such a deep protagonist is capable of triggering a strong immediate reaction that each of us would like to enact at least once in our lives.

Yousef Wakkas “Sulla via di Berlino”

(Cosmo Iannone, 2017)

In this “forced March”, the author stages surreal catastrophes through imaginative metaphors of psychological disorientation, personal and collective traumas, capturing the essence of the Middle Eastern world, the allure of galleys and galley ships, viziers and grand sultans, and the poetry of distant times that betrayed their promises of happiness. Her storytelling gives voice to the wandering in the nightmare of losing every human reference, chronicling the atrophy of reverting, somehow, for those who have lived as humans, to the constraint of returning to the primordials in the inferno of bestiality. Nadia, Milad, Àdel “the melancholic warrior,” are all protagonists of a complex and passionate novel that guides us into the tragic senselessness of war, of every war, in every era, and testifies to and narrates, like few others, our contemporary reality.

Bijan Zarmandili “Storia di Sima”

(Nottetempo, 2016)

With her irregular beauty, emotional opacity, and an aura of indifference towards life, the protagonist of Bijan Zarmandili’s new book is as enigmatic and unsettling as a sphinx. The mark of Sima is her strabismus of Venus: a sign of detachment from things and a deviation of the gaze that makes her even more impenetrable, as if fate were written in her eyes. Born to a wealthy couple of expatriate Iranians in London, Sima grew up in a cushioned, affectionless environment, with a depressed mother and a father absorbed in his stock market affairs. In Rome, where she arrived to escape her family, she built herself a small bourgeois nest with Stefano, a wealthy architect met at university, and their son Dario. But Sima was not meant for idyll; the “Stranger” – always distant, always elsewhere – eventually succumbs to the call of her demons.

Abdoulaye Thiam “Africa allo specchio”

(Edizioni del Gattaccio, 2019)

Sembe, a Senegalese immigrant in Italy, returns to his homeland for his mother’s funeral. This return after many years has a profound impact on him: his experiences growing up in the Casamance region, where animism peacefully coexists with Islam and Christianity, raise questions about the traditional practices still in place, but also highlight that nothing is ever fixed over time and that evolution and new syntheses are the norm. Sembe reflects on how globalization does not fully account for either the identity of peoples or the individuality of people. The clash between the two cultures present in his life (African and European) causes a shock from which his friends try to help him emerge.

Asmae Dachan “Il silenzio del mare”

(Castelvecchi, 2017)

A novel drawing from the dramatic reality of the Syrian war. Two brothers, Fadi and Ryma, join the secretive pacifist movement that emerges on university campuses and engages young people and workers. They take active steps to defend human rights, dreaming that Syria will regain freedom and break free from dictatorship oppression. It’s 2011, and their dream quickly fades. Discovered and threatened by the regime, they are forced to flee the ensuing brutal war, which is compounded by the horrors of terrorism. They embark on a journey from Libya to Italy, but during the crossing, a tragedy occurs and Fadi arrives ashore alone. Ryma’s fate remains shrouded in the silence of the sea. In Italy, the young Syrian is taken in by a fisherman and a young doctor. Their destinies intertwine unexpectedly. Each seeks answers in the other, and as death continues in Syria, an unexpected event disrupts Fadi and his friends’ new lives.

Nadeesha Uyangoda “L’unica persona nera nella stanza”

(66th and 2nd, 2021)

Race is a challenging concept to grasp, yet it has profound effects on social, professional, and romantic relationships, despite having no biological basis. In Italy, race doesn’t become apparent until you’re the only black person in a room full of whites. And that single person is Bellamy, Mike, Blessy, David… a multitude that is in part submerged, underground. That single person is one who has been told too many times that “black Italians do not exist”: this is shouted in stadiums, it is stated by certain politics, it seems confirmed by TV series, literature, and the media. In a way, it is even true: black Italians do not emerge, they are not seen in cultural environments, talk shows, or electoral lists. Or rather, they exist in these places but only as objects of discourse, almost never as subjects. Their presence is limited to citizenship reform, cases of racism, “out-of-control immigration,” boats, and “integration.” With an innovative approach and a fresh, “social” language, Nadeesha Uyangoda opens an honest conversation in this book, blending essay and memoir, to better understand the racial dynamics in our country.